- Buy from Elliot Bay

- Buy from Powells

- Buy from Amazon

- Buy from BookSense

(and support your local bookstores)

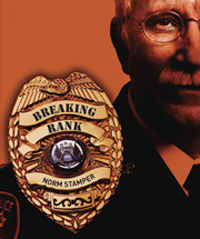

Norm Stamper, former chief of the Seattle Police force, has written a story like no other. Part-memoir, part polemic, Stamper exposes the unvarnished truth — both disturbing and inspiring — about policing in America today.

Breaking Rank

A Top Cop's Exposé

of the Dark Side of American Policing

Norm Stamper

Seeing Red

by Neal Matthews | San Diego Union-Tribune

May 29, 2005

Former SDPD officer Norm Stamper's memoir Breaking Rank is an angry eye-opener about police culture

Norm Stamper earned this book. His career in law enforcement spanned a reformist era in policing, and he was a reformer. For 30 years he moved upward against the grain of traditional police culture, most of it as the resident liberal of the San Diego Police Department.

Stamper was passed over for chief here when Jerry Sanders got the job in 1993, and he became police chief in Seattle in 1994.

Six years later, his career went down in the flames of the World Trade Organization riots, when his department was shown to be embarrassingly underprepared to prevent civic chaos.

Unreconstructed cops everywhere enjoyed a nip of schadenfreude at Stamper's expense, but he seems to have retired to the San Juan Islands without much bitterness. Now comes his memoir, "Breaking Rank," which manages to avoid score settling but still strips away the carapace of police culture to confirm some of our worst fears about the way power is wielded behind the badges.

"Even today," Stamper writes, policing "serves the interests of politicians over 'the people,' landlords over tenants, merchants over consumers, whites over blacks, husbands over wives, management over labor – except when 'labor' is the police union."

Coming from a lefty egghead, this would be predictable ranting. But reading page after page of penetrating (but always constructive) criticism coming from a former police chief is like going on a bender with a get-out-of-jail-free card. I wanted to stand up waving a lighter as I read passages detailing police racism, homophobia and hatred of political dissidents, and Stamper's radical notions of reform – like doubling police pay to $100,000 a year.

"The paramilitary bureaucracy" of police departments, Stamper writes, "is a slow-footed, buck-passing, blame-laying, bullying, bigotry-fostering institutional arrangement, as constipated by tradition and as resistant to change as Mel Gibson's version of the Catholic Church. I cannot imagine other essential reforms in policing – improved crime-fighting, safety and morale of the force, the honoring of constitutional guarantees – without significant structural transformation."

Using as a structural skeleton his own transformation from a bigoted rookie to an outspoken reformer, Stamper knits together chapters that roam widely from policing domestic violence to the power that police unions have to strangle reform. He also lays into what he believes underlies the worst impulses of police culture – bad laws.

"By any standard, the United States has lost its war on drugs," Stamper writes. His solution: decriminalization of most forms of dope. He sees it as a question of free will for adults to be able to decide for themselves what to ingest in the privacy of their homes, as well as a way to attack a form of structural racism that refracts from society and tilts the justice system. "[P]oor blacks smoke cheap crack, upscale whites snort the spendy powdered version of cocaine. And who goes to jail? For longer periods of time? Blacks, of course." And then he backs up his argument with solid statistics.

He also thinks prostitution should be moved from the streets and made legal if practiced indoors, and that capital punishment is a cruel failure with no value as a deterrent to crime. He cites evidence of race and class discrimination in meting out the death penalty, the incompetence of public defenders, the higher cost of execution vs. lifetime incarceration, and the fact that as of 2003, 132 people who had been sentenced to die have been found to be innocent.

He calls execution "the coward's way out." "How can we justify killing someone whose threat has ended with incarceration? In my mind it's an extension of the mentality of child abusers who know their victims can't fight back. Or of a cop who beats a handcuffed prisoner."

In many of his short, sometimes too-sketchy but always engaging chapters, Stamper uses local cases to help make his points. So we get to revisit, from a cop's perspective, the two cop killings in September 1984 by Joselito Cinco in Grape Street Park, and the serial prostitute murders of the late 1980s that involved some locally prominent people and ignited the career of prosecutor (now district attorney) Bonnie Dumanis. Stamper has a gift for scene-setting and storytelling, and his insider's perch adds some valuable missing pieces that help round out San Diego's late 20th-century history.

Stamper makes a lot of unflattering admissions in this book: to brutalizing people who gave him lip as a rookie cop, to an addiction to pain medication, to drinking confiscated booze after hours at headquarters with other police brass. (SDPD HQ is now dry.) He's also painfully candid about his killing of an unarmed man in University Heights. But when he fesses up to being a member of the department's notorious Red Squad of undercover operatives, he adds important new information to the history of the antiwar movement here.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, SDPD's "dirties" were part of the large-scale official effort (it included the FBI and other law enforcement agencies) to infiltrate and spy on local anti-Vietnam War activists, the Black Panthers and far-right bomb throwers. The chapter on his year working undercover as a spy in the Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) chapter at UCSD is by turns harrowing, funny and sad. Stamper says he is ashamed of what he did, given his basic sympathy with the antiwar cause. "How could I spy on my ideological allies?" he asks himself. He reports that most of his police colleagues wrote off all antiwar protesters as "rich spoiled brats or social misfits. As individuals, some of them may have been just that, but most of the people I befriended and spied upon were among the most dedicated, hardworking, and morally upstanding I've ever met."

Technically, Stamper broke the law when he took part in the student takeover of the UCSD registrar's office in 1969 at the height of the fervor involving leftist professors Angela Davis and Herbert Marcuse. The two of them had been red-baited relentlessly by San Diego media – which reflected the stark conservatism of most of the community, to be sure – and Stamper spent much of his time trying to sniff out rumors about people planning to attack the professors.

The story of his undercover experience, which includes organizing a troop of armed undercover narcs to attend a rally at UCSD in order to prevent a supposed assassination attempt on Davis, is fascinating, as far as it goes. But Stamper doesn't have much to say about other undercover informants who committed serious crimes while on the police and the FBI payroll, though he does use those abuses to argue against the post-9/11 pressure on police agencies to start spying again on peaceful protest groups.

"In police work you get all kinds of chances to choose between two wrongs: do something when you should do nothing, do nothing when you should do something," Stamper writes. In many places throughout the book he is searingly honest about actions that seem abhorrent – like spying on friends and harassing gays in Balboa Park – but you end up feeling sympathetic because he seems to gain insight and even wisdom from his experiences. His reformist zeal does go to his head a little bit, as when he devotes a whole chapter to his disillusionment with the press (based on some rough treatment in the Seattle papers). And he edges toward pomposity when he starts lecturing on sole-source reporting and the use of anonymous quotes.

This good book could have been marvelous had Stamper kept to his spare, anecdote-based peregrinations on hard-won lessons from the front lines, and not bloviated in chapters about the press, community policing and the need for better police leadership. But these are quibbles; Stamper's passionate voice of reason deserves a place in the annals of police reform.

Opening with a powerful letter to former Tacoma police chief David Brame, who shot his estranged wife before turning the gun on himself, Stamper introduces us to the violent, secret world of domestic abuse that cops must not only navigate, but which some also perpetrate. Stamper goes on to expose a troubling culture of racism, sexism, and homophobia that is still pervasive within the 21st century force, exploring how such prejudices can be addressed. He reveals the dangers and temptations that cops on the street face, describing in gripping detail their split second life-and-death decisions.